The Mets keep telling you they’re looking for pitching. The real story is who they’re willing to cut loose to get it.

Fans love the idea of “adding a starter.” Sounds clean, simple, like you just walk into the store, grab a gallon of innings, pay at checkout, go home. That’s not what this is.

This is roster conversion. This is the Mets looking at a crowded infield room and saying, “Cool, which one of you turns into 170 innings without wrecking our future payroll?”

What “trade-first” actually means

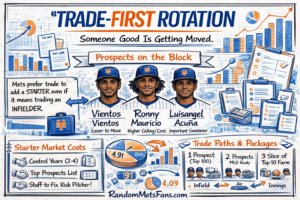

“Trade-first” is not a vibe, it’s a constraint. The reporting is clear: the Mets prefer to upgrade the rotation via trade rather than free agency, and three young infielders have been identified as available in talks: Mark Vientos, Ronny Mauricio, Luisangel Acuña.

That’s not random. That’s a signal.

Free agency costs money and years, trades cost talent and depth. If you are allergic to long-term pitching contracts, you pay in players.

The real reason the Mets are doing it this way

1) The contract horizon is getting guarded like a nuclear code

Long starter deals age like milk. Every front office knows it. The Mets have acted like it. Shorter commitments keep the future clean. Trade acquisition lets you buy innings without marrying them.

2) The Mets have prospect leverage, not unlimited money leverage

This farm is not a joke right now. Multiple outlets have them as a Top 10 system. More importantly, the Mets have a cluster of prospects that other teams actually want to build around.

Here’s the key: teams do not trade real starting pitching for “nice depth.” They trade it for players they think can start for them soon.

3) The innings math has been a problem

In 2025, Mets starters averaged 4.91 innings per start. That’s not a flex, that’s a bullpen tax.

Do the simple math. A nine-inning game minus 4.91 means your bullpen is covering roughly 4.09 innings a night on average. That is a long season way to lose your relievers in August, then pretend it was “bad luck.” A trade-first rotation plan is a direct response to that reality.

The names are out there for a reason

Let’s stop treating Vientos, Mauricio, and Acuña like they’re three identical “young guys.” They are three different trade assets with three different markets.

Mark Vientos: the cleanest “bat for innings” chip

What he is: Power and damage potential.

What he is not: A defensive solution that makes everyone sleep better.

Contending teams buy bats, rebuilding teams buy controllable bats. Vientos fits both, which makes him the easiest to move.

Front-office translation: Vientos is the most likely piece to headline a deal if the Mets target a starter with years of control.

Ronny Mauricio: the upside swing that makes GMs drool and fans panic

What he is: Tools, ceiling, switch-hitting potential, defensive versatility.

What he is not: A finished product you can pencil into “everyday certainty.”

Mauricio is the “dream” asset in a trade, which is exactly why fans hate seeing his name in rumors. Upside feels like hope, hjope feels like identity. Trading that feels like betrayal.

The Mets will move him if they think the rotation target is more certain than the player development outcome.

Luisangel Acuña: the sweetener that can become the lead if the target is right

What he is: Speed, athleticism, middle-infield capability, real baseball traits.

What he is not: A guaranteed impact bat today.

Acuña plays in the currency of “useful.” Teams love useful and players let a GM sell a trade to the public as “we got a real major leaguer back,” even if the deal is ultimately about the pitcher.

If you see Acuña included, it often means the Mets are trying to avoid paying the premium prospect price with their top tier.

The Top 100 prospect angle matters more than fans want to admit

This part is not a fun conversation, but it’s the truth.

The Mets have multiple prospects being discussed in Top 100 terms, including Carson Benge, Nolan McLean, Jonah Tong, Jett Williams, Brandon Sproat. That matters because starting pitching deals usually require at least one piece the other team can market as a future cornerstone.

One of two things is going to happen:

- The Mets move an established young big leaguer type (hello, Vientos) plus secondary talent.

- The Mets move a Top 100 prospect plus a “now” piece, then Mets fans spend two months yelling into the void.

No third door exists if the target is a legitimate starter.

What kind of starter fits this plan

A “trade-first” approach tells you the profile. This is what makes sense:

Tier 1: Controlled starter, 2–4 years of team control

This is the pitcher that costs the most. This is the pitcher that forces the Mets into painful decisions.

The return usually looks like:

- One headline piece (Top 100 prospect or young MLB bat)

- One secondary prospect with real upside

- One lottery ticket arm

Tier 2: Mid-rotation innings eater, dependable 160–190 innings

This is the adult in the room. Fans complain because it isn’t sexy. Managers love it because it saves the bullpen.

The return usually looks like:

- One young MLB-ready position player

- One mid-tier prospect

Tier 3: High-variance starter with stuff, risk, and a “we can fix him” pitch

This is where teams talk themselves into being the smartest guys in the room.

The return usually looks like:

- Two good pieces, less headline value

- More volume, less certainty

The Cabrera trade just changed the market, and it matters

One meaningful trade can reset the baseline. Edward Cabrera coming off the board thins the supply and tells every other seller, “See that package? Start there.”

That is why this Mets story is not really about “do they want pitching.” They want pitching. Everyone wants pitching.

The question is pricing, and whether the Mets will pay it with:

- Vientos and friends

or - a Top 100 prospect that fans have already tattooed to their brains

The whiteboard version, the one Stearns actually cares about

Goal: Add starter innings without adding long-term dead money.

Constraint: Starter market is thin, prices are inflated.

Leverage: Top-10 farm reputation plus infield surplus.

Guardrails:

- No panic trades for a name.

- No emptying the top of the system for a rental.

- No pretending the bullpen can carry 4+ innings a night again.

Who is most likely to get moved

If you forced me to rank it purely on roster logic and trade value:

- Vientos

- Mauricio

- Acuña

That ranking flips if the Mets target changes.

A deal for a more controllable, higher-end starter pulls Mauricio up the board fast. A deal for an innings eater pulls Vientos to the top, with Acuña as a likely add-on.

What this means for 2026

This is not about “winning the offseason.” This is about winning Tuesdays in July.

A trade-first rotation plan is the Mets admitting a simple truth: the team cannot keep playing five-inning starter baseball and expect the bullpen to stay alive. The price to fix it is not cash.

The price is a player you have already argued about online.

Why this matters for Mets fans

This is the fork in the road. One path keeps the infield logjam and hopes the pitching sorts itself out. That path ends with tired relievers, patchwork spot starts, and that familiar smell of late-season collapse.

The other path turns surplus into innings. It costs something. It also looks like how serious teams operate when the market is ugly.

The Mets are telling you what they plan to do. The next move tells you how bold they are willing to be.

Resources

- Mets prefer trade market for rotation upgrades, Vientos/Mauricio/Acuña available, Top 100 prospect mentions.

- Starters innings problem, Mets starters averaged 4.91 IP per start in 2025.

- MLB Pipeline Mets prospect context and “new wave” of top names.

- Mets system “best tools” report with Benge and Jett Williams notes.