There are bad trades, and then there are trades that permanently change how a fan base trusts its team.

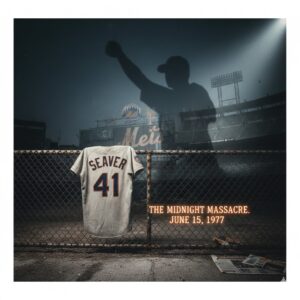

For the New York Mets, that moment came on June 15, 1977, the night the franchise traded away Tom Seaver. Not because he was declining, not because he was expendable, but because ownership decided it would rather win an argument than win baseball games.

This wasn’t just a transaction. It was a rupture.

Seaver wasn’t just the Mets’ ace, he was the franchise’s spine. The reason people believed the Mets were legitimate. The one player who made Shea Stadium feel like it mattered, and in one cold, late-night decision, the Mets told their fans that loyalty, excellence, and history were negotiable.

That’s why this trade still hurts. That’s why it still gets talked about by so many Mets fans. That’s why, nearly 50 years later, it remains the single most defining mistake in Mets history.

Go ahead, prove me wrong in the comments section.

For Mets fans, that trade happened on June 15, 1977. Late at night, when all the Mets fans were tucked away in their bed, a deal was announced so late it earned the name “The Midnight Massacre,” the Mets sent Tom Seaver to the Cincinnati Reds for Pat Zachry, Doug Flynn, Steve Henderson, and Dan Norman.

That sentence still looks wrong on the page as I type it.

Seaver wasn’t just the Mets’ ace. He was the freakin’ Mets. A Three time Cy Young Award winner. The face of OUR franchise. The guy who made the Mets feel legitimate in a city that loves winners and has no patience for excuses. When the team won in 1969, he wasn’t a piece of the story, Seaver was the story.

So why did the Mets do it? Let’s break it down and at the end, let’s see if it really mad sense.

It all starts with the Mets, in 1977, were a franchise run more like a grudge match than a business.

The setup: a last-place team with a first-place ego problem

By mid-June 1977, the Mets weren’t competing for anything except headlines. They were a losing club with internal chaos, a roster that was thinning out, and an ownership group that still acted like the 1969 banner should cover every mistake forever.

Seaver was 32 and still pitching at a high level, but what mattered most to the Mets’ leadership wasn’t his ERA, it was his contract, and the relationship between Seaver and the men running the Mets had turned toxic.

Tom Seaver’s Production Before the Trade (1967-1976)

| Category | Stats |

|---|---|

| Games Started | 349 |

| Wins | 198 |

| ERA | 2.86 |

| ERA+ | 127 |

| WAR (Baseball-Reference) | ~62.1 |

| Cy Young Awards | 3 |

| Top-5 Cy Young Finishes | 6 |

| Innings Pitched | 2,500+ |

The public face of that toxicity was M. Donald Grant, the Mets’ board chairman and a symbol of everything fans hated about the old guard: stubborn, cheap, prideful, and bizarrely confident he could outmuscle a superstar in New York.

Seaver wanted to be treated like the franchise cornerstone he was. The Mets wanted to “win” the negotiation, a pound my chest moment for Mets management. That’s how this becomes personal, and once it becomes personal, logic stops showing up to work.

By the time June rolled around, the feud had spilled into the papers. It wasn’t subtle, it wasn’t private, but it sure was messy, loud, and humiliating. The longer it went, the more you could feel the franchise drifting toward the cliff edge.

“The Midnight Massacre”: how the deal actually happened

The Reds were coming off a powerhouse era and were built to win now. They wanted an ace who could take the ball in October and end games. They also weren’t scared of the price.

So, on June 15, they got their guy. The Mets sent Seaver to the Reds and received four players in return. None were stars, but they did have potential. None were Seaver, and that matters, because Mets fans weren’t just losing THEIR pitcher. They were losing the one thing that made the Mets feel like a serious organization.

This is where the emotion becomes the point. Baseball is business, sure, but fanhood is identity, especially in New York. Seaver was OUR Mets identity. That’s why the reaction was nuclear.

Fan sentiment: It was grief, rage, & the feeling of being betrayed

This wasn’t “angry fans on talk radio.” This was raw. People actually cried. There is nothing that scars you for life that watching your Grandpa crying in HIS chair as the news broke. People threatened management, like Mafia style threating – broken legs, noses, ending up the river kind of stuff. People stopped going to games, and not in a symbolic way.

Attendance collapsed. Shea Stadium, a place that once shook in October, became a mausoleum. It got so bad that by 1979, the Mets were averaging under 10,000 fans per game. In New York, for a Major League baseball team, that’s not a dip, that’s a franchise in free fall.

It also wasn’t just the trade. It was what the trade represented.

It told fans, loudly: We will choose pride over winning. We will choose control over loyalty. We will trade the franchise icon to prove a point. Good luck selling hope after that.

Mets’ logic: “We need pitching depth and we can’t pay everyone”

If you want to be fair, you can build the Mets’ argument like this – so stay with me on this one, ok :

- Seaver was 32, not 25.

- They were going nowhere in 1977.

- They needed multiple pieces, not one star.

- Pat Zachry was young and had pedigree (1976 NL Rookie of the Year, World Series champion).

- Doug Flynn was a glove-first infielder who could stabilize a defense.

- Henderson and Norman were outfield depth.

On a chalkboard, that looks like “retooling.” In real life, it was the front office trying to make a superstar problem disappear without admitting they created it, and analytically, it didn’t hold up.

Because a trade like this only works if the return gives you either:

- a comparable star, or

- a pile of production that adds up to a star.

The Mets got neither.

On-field results: Seaver stayed great, the Mets stayed miserable

What Seaver did after the trade

Seaver didn’t fade, he didn’t crumble, he didn’t turn into some “old 32” cautionary tale. He went to Cincinnati and immediately reminded everyone what an ace looks like when he’s motivated.

Over his Reds run (1977–1982), he went 75–46 with a 3.18 ERA, and in 1978 he threw the only no-hitter of his career, mind you, no Mets pitcher had ever thrown a no-hitter at this time, so this one stung a little more. In the strike-shortened 1981 season, he went 14–2 and was right in the Cy Young conversation again.

Seaver with Reds (1977–1982):

- WAR: ~30

- ERA: 3.18

- Cy Young votes: multiple top-5 finishes

- 1978: 16–7, 2.88 ERA

- 1981: 14–2, 2.54 ERA

- Threw a no-hitter in 1978

This is the key analytic point: the Mets didn’t trade a declining asset. They traded a still-elite one, and too many fans, got diddly squat in comparision.

What the Mets got

Now let’s look at the return like a front office would today, not like a press release would in 1977.

Pat Zachry

Zachry was the “headliner,” and for a brief moment he looked like he might justify the deal. He made an All-Star team as a Met in 1978, and he had stretches where he was a credible mid-rotation starter.

But that’s the problem. In a trade where you’re giving up Tom Seaver, “credible mid-rotation starter” is not a win condition. It’s the consolation prize you accept when you already lost.

Zachry also dealt with injuries and inconsistency in New York. His Mets tenure ended as more of a “what if” than a foundation.

Stats (1977–1984 Mets tenure)

- WAR: ~7.6 total

- ERA with Mets: 3.96

- Best season: 1978 (3.36 ERA)

- Role: Mid-rotation starter

Doug Flynn

Flynn was defense only, that’s it. A glove-first infielder who later won a Gold Glove in New York. F;ynn was a useful player, sure, but defense-only players don’t replace aces, and they don’t sell tickets, and they sure as shit don’t stop a franchise from collapsing in on itself.

Stats

- Career WAR with Mets: ~4.4

- OPS+ with Mets: 69

- Defensive specialist, limited offensive value

Steve Henderson

Henderson could hit. In fact, he hit well as a Met, but he wasn’t a star, and the Mets, desperate for power, often tried to force him into being one. That matters, because it’s a reminder of where the organization was: constantly trying to duct-tape its way out of bigger problems.

Stats

- Career WAR with Mets: ~4.6

- Best season: .281 / 12 HR (1979)

- Never an All-Star

Dan Norman

Norman didn’t move the needle at all, as my grandpa would, “He was a bum.” However, for the Mets, he added depth. He was filler, and that’s exactly what you can’t afford when you trade a Hall of Fame ace like Seaver.

Stats – Well, never mind

- Essentially replacement-level player

The team impact

The Mets didn’t stabilize. They cratered.

They finished last the next three seasons after Seaver was traded. They didn’t have a winning record again until 1984. Let’s math that up a little. That’s seven years in a row, Mets fans had to deal with a shit team. This wasn’t a “step back to step forward.” It was a long, ugly tumble.

There’s the punchline that makes it worse: the pitching didn’t even improve. If your justification as an organization is “we need arms,” and the result is still losing and still pitching problems, then the trade failed on its own terms, period, end of story.

The real cost: not WAR, not ERA, not even wins

The cost was trust. A franchise survives bad seasons. Fans can deal with losing when they believe a plan exists. However, when fans believe the people running the team don’t respect them, don’t respect winning, and don’t respect the players who built the brand, that’s when you get empty seats and a civic-level grudge.

That’s what Seaver’s trade did. It taught Mets fans the darkest lesson: The Mets can hurt you even when you’re right.,and if you’re building a series around “top trades,” this is where you start because it’s not just a baseball move. It’s a cultural wound!

Why the trade failed, in one clean analytic sentence

The Mets traded an elite, still-productive ace for a package of decent role players and a mid-rotation arm, and the combined return never approached the value Seaver continued to provide. That’s the whole story.

Everything else is the fallout.

The Raw Math (This Is Where It Gets Ugly)

| Category | Mets Received | Seaver Alone |

|---|---|---|

| Total WAR | ~16–17 | ~33 |

| Peak Performance | No | Yes |

| Franchise Value | Low | Extremely High |

| Fan Engagement Impact | Negative | Massive |

| Long-term ROI | Poor | Elite |

The ending, because Mets history always gives you one more twist

Seaver eventually returned to the Mets in 1983, which felt like the universe trying to apologize to Mets fans across the country. It helped, a little. It mattered, a little, but it didn’t erase what happened.

“The Midnight Massacre” still lives in Mets DNA as the example of what happens when ego runs the front office. Hmmmm, sound familiar for current Met fans right now?

Bad trades are part of baseball. This wasn’t just a bad trade. This was a franchise telling its fans, “You don’t get to keep your heroes,” and Mets fans have never forgotten it.

The Analytics Verdict

Using modern evaluation logic:

- Seaver’s WAR per season (1977–1981): ~5.5

- Average return per player (combined): ~1.0–1.5 WAR

- Efficiency ratio: Mets received roughly 30–40 cents on the dollar

No contender makes that trade. No rebuilding team should make that trade. No front office acting rationally makes that trade.

This wasn’t a baseball decision. It was a political one.

The Final Verdict

Was the Seaver trade defensible?

No.

Was it understandable emotionally?

Maybe.

Was it catastrophic strategically?

Absolutely.

This wasn’t hindsight bias. Even at the time, the numbers didn’t support it. History just made the lesson impossible to ignore.

What’s next in the series

The Seaver trade didn’t just damage the Mets in the standings, it reshaped how the organization thought about loyalty, leverage, and the cost of being wrong. It was the moment the Mets stopped protecting their foundation and started gambling with it.

The lesson should have been clear: you don’t trade away greatness and expect to replace it with parts.

But the Mets didn’t learn that lesson. Just a few years earlier, they had already made another deal built on the same flawed logic, another move where they convinced themselves that depth was safer than dominance, and that a superstar was expendable if the return looked “balanced” on paper.

That trade involved a young flamethrower named Nolan Ryan, anyone remember him, for a veteran infielder named Jim Fregosi.

That’s where this series goes next.

👉 Subscribe to get the next chapter delivered straight to you.

Join the conversation, argue the history, and help decide which Mets trade hurt the most.